BBC News, Yorkshire

Science correspondent, BBC News

York University

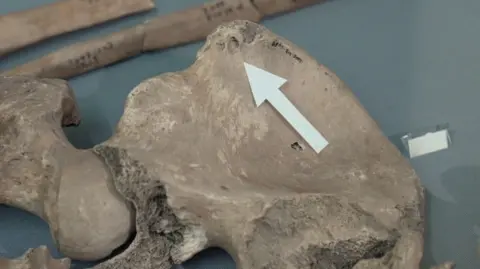

York UniversityThe bite marks found in the skeleton of a Roman gladiator are the first archaeological evidence of combat between a human and a lion, experts say.

The remains were discovered the duration of a 2004 excavation in Driffield Terrace, in York, a site that is now believed that it is the only cemetery of a well preserved Roman gladiator in the world.

The forensic examination of a young man has revealed that the holes and bite marks in his pelvis were probably caused by a lion.

Professor Tim Thompson, the forensic expert who directed the study, said that this was the first “physical evidence” or gladiators fighting against great cats.

“For years, our understanding of the fight of Roman gladiators and animal shows has largely related historical texts and artistic representations,” he said.

“This discovery provides the first direct physical evidence that such events took place in this period, remodeling our perception of Roman entertainment culture in the region.”

Experts used new forensic techniques for wound analysis, including 3D explorations that showed that the animal had grabbed man by the pelvis.

Professor Thompson, from the University of Maynooth, in Ireland, said: “We could say that the bites occurred around the moment of death.

“So this was an elimination of animals after the individual died, he associated with his death.”

In addition to scanning the wound, scientists compared their size and shape with samples of large cat stings in the London Zoo.

“Bite brands in this particular individual coincide with those of a lion,” Professor Thompson told BBC News.

The location of the snacks of great researchers with uniform information about the circumstances of the gladiator’s death.

The pelvis, Professor Thompson explained, “it is not where the lions normally attack, so we believe that this gladiator was fighting in some kind of show and was incapacitated, and that the lion bit him and dragged him to the hip.”

Getty images

Getty imagesThe skeleton, a man between 26 and 35, had been buried in a grave with two others and exaggerated with horses.

The previous analysis of the bones pointed out that it was a bestiarius, a gladiator who was sent to the fight with beasts.

Malin Holst, a professor of osteoarcheology at the University of York, said in 30 years of skeletal analysis that “I had never seen anything like these bite brands.”

In addition, he said that the remains of man revealed the history of a “short and somewhat brutal life.”

His bones were formed by large and powerful muscles and there were evidence of shoulder injuries and spine, which were associated with a hard and combat physical work.

Mrs. Holst, who is also managing director of York Osteoarchaeology, added: “This is a very exciting finding because now we can start building a better image of how these gladiators were in life.”

The findings, which have been published in the Journal of Science and Medical Research Plos One, also confirmed the “presence of large cats and other exotic animals enhanced in sands in cities such as York, and how the death of the threat of the termelvos of said.

The experts said that the discovery added weight to the suggestion of an amphitheater, although it has not yet been found, it probably existed in Roman York and would have organized the fighting gladiators as a form of entertainment.

The presence of distinguished Roman leaders in York would mean that they required a luxurious lifestyle, experts said, so it was no surprise to see evidence of gladiatic events, which served as a sample of wealth.

David Jennings, CEO of York Archeology, said: “We may never know what led this man to the sand where we believe he can have bones fighting for the entertainment of the ethers, but the first osteo is remarkable -School away from the Colosseum of Rome, which would have been the combat stadium of the classical world.”