Music correspondent

BBC

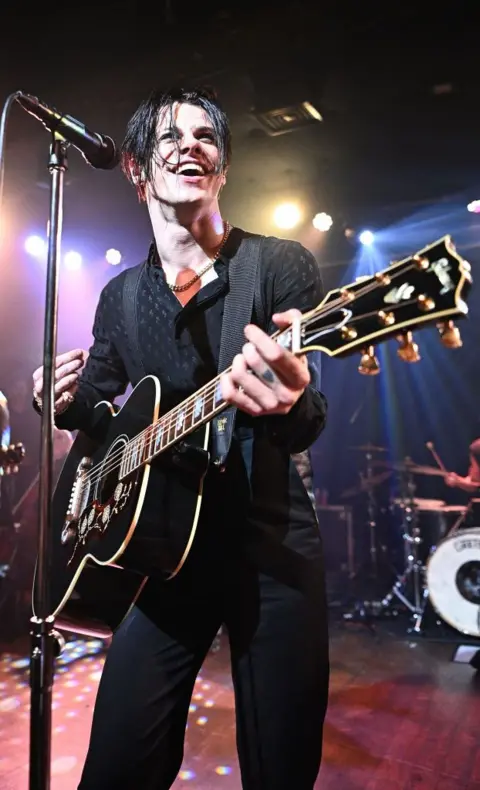

BBCNetherlands, March 2025. Yungblud leaves his hotel in Amsterdam when a fan is approached in floods of tears.

“You saved my life,” he sobbed.

“No, you saved your own life,” he replies, in silence. “Maybe music was the soundtrack, but you saved your life, okay?”

Leaning for a hug, he adds: “Don’t be sad, be happy. I love you.”

It is a remarkable moving moment, full of compassion and ego of dark star or rock.

Two weeks later, after a video of the match goes viral, Yungblud still moves through memory.

“I didn’t think people see that, except me and me,” he says, “but it was a time for me.”

The interaction crystallized something I had felt for a while.

“I always said that Bowie and my chemical romance saved my life, but finally you have to find yourself,” he says.

“Like this morning, I put on the headphones and listed to [The Verve’s] Sortunate man, and made me go, ‘Oh, I’m ready to face the day’.

“But Richard Ashcroftt didn’t tell me that I was ready to face the day. I told myself.

“That is what I was trying to tell that girl in Amsterdam.”

Getty images

Getty imagesSelf -confidence is a lesson that learned in the difficult way.

On the surface, Yungblud, also known as Dominic Harrison, 27, had everything. Two number one albums, a base of international fans, a documentary by Louis Theroux and sufficient influence to direct its own festival.

But if you seemed more closely, there were cracks in the armor. Those number one albums fell from the top 30 after a week, a sign of a Strong Core fans base, with a limited cross attraction.

And the first year of his Bludfest in Milton Keynes was criticized after long lines and the lack of water caused fans to pass out and miss the concert.

Harrison was very aware of everything. When he launched his third homonym album in 2022, he has reached a bass.

“Yungblud was number one in seven countries, and I was not happy because it was the album I wanted to do,” he says.

“It was a good album, but it was not exceptional.”

The problem, he says, was a record label that had pushed him in a more commercial direction. But by polishing his sound, he lost the angry unpredictability that characterized his best work.

“It’s funny, my own album was real in which I was more lost,” he observes.

“I felt that I committed myself, but, for that, I never returned to a bar not for an answer.”

Nowhere is it so clear that in his single back, Hello Heaven, Hi.

Approximately nine minutes and six seconds, it achieves excess levels of calligulant, full of scoring guitar alone, vocal races of crushing throat and even an orchestral coda.

“Do you still remember or have you forgotten where you are from?“Harrison asks himself, while attending his ambition again.

The song is intentionally inappropriate for the follow -up single, Loveick Lulaby. Released today, it is a free association fuss through a messy night, which ends with the epiphany in the drug trafficker apartment.

Combining the mockery of Liam Gallagher with the harmonies of Beach Boys, it is exclusively Yungblud. But the singer reveals that he was originally written for his last album.

Locomotion / Universal

Locomotion / Universal“We really discourage us from doing it,” he says.

“My advisor at that time, a boy named Nick Groff [vice president of A&R at Interscope, responsible for signing Billie Eilish]It was like, “I don’t understand it.”

To the heating of the theme, he continues: “The music industry is shit because it is money, but, as an artist, I need to make sure that everything that publishes is exciting and unlimited.

“It can’t be like a 50% or me version.”

To achieve that, he rejected the expensive recording studios and made his new album in a Tetley brewery turned into Leeds.

Professional composers were also banished, in favor of a nearby group of collaborators, including guitarist Adam Warrington, and Matt Schwartz, Israeli-British producer who directed his debut in 2018.

“When you make an album in Los Angeles or London, everything is great, it is even mediocre, because people want a success,” he argues.

“When you make an album with the family, all of them because it is the truth.”

‘Lord and Liberation’

One of the most honest tracks on the disc is Zombie, a ballad of lighters (think of Coldplay, sung by Bruce Springsteen) about “feeling that you are ugly and learn to fight with that.”

“I was always insecure about my body, and that stood out when I became famous,” says the singer, who last year revealed that he had developed an eating disorder due to body dysmorphia.

“But I realized that the greatest power that you can give up is how you react. So I decided that I am sober, I’m going to put on shape and discovered boxing.”

He ended up working with the South African boxer Chris Heerden, who was recently in the news after Russia imprisoned her dancer’s girlfriend, Ksenia Karelina.

“I with him before all that,” says Harrison, “but has been extremely inspiring. Boxing becomes therapy for me.

“Some say something bad about me, I go to the gym, I arrive at the bacaltant for an hour and speak it.”

Fans have noticed the change … drooling about photos of their freshly chiseled torso and declaring their “shirt era” 2025.

“Maybe the era of the shirt is a return to all the comments I have,” he laughs.

“I am claiming a freedom, a sensuality and a liberation.”

Getty images

Getty imagesHe has clearly found a certain degree of serenity, without delivering the restless energy that promoted him to fame.

Part of that is due to control. In January, he created a new company that brings together its main music business recorded with tour operations, its fashion brand and its Music Festival, Bludfest.

The event began in Milton Keynes last summer, but suffered dentition problems, when fans were trapped in long lines.

“I will assume the responsibility of that,” says the star, who states that he was “shouting, the police and the promoters between the reasons for the lines so that the lines move.

“The problem was that there were six open doors when you should have the leg 12,” he says, suggesting that people underestimated the dedication of their fans.

“When Chase and the State had played [there] A day before, there were 5,000 people when they opened the doors and another 30,000 trick clothes on the day of the day.

“With my fans, there were 20,000 children at the door at 10 am

The dedication to his fans is what makes Yungblud Yungblud.

He built the community directly from his phone and, whether planned or not, that connection has sustained his career, isolating from the tyrannies of the radio playback lists and the transmission placement.

Maintaining a personal relationship becomes more difficult as its fans base grows, but, always cunning, hired a fan to supervise their social accounts.

“It’s called Jules Budd. I used to my concerts in Austin and sold Confeti to pay the gas money to the next city.

“She builds an account called Yungblud Army, and it’s incredible to let me understand what people feel.

“If people are outside and security does not treat them well, I know why he is in contact with them. So I brought to make the community safer as it becomes bigger.”

With his new album, hey, so that this community is equally bigger. Backing to the sounds of Queen and David Bowie, he says that “he will claim the good chords” (ASUS4 and EM7, in case you are asking you).

“The shackles are turned off,” he smiles.

“We made an album to show our ambition and the way we want to touch.

“Can you imagine see Yungblud on stage? 100% yes. Let’s do it.”