BBC environment correspondent

Getty images

Getty imagesAn innovative project to suck carbon outside the sea has begun to operate on the southern coast of England.

The small pilot scheme, known as Seacure, is funded by the United Kingdom government as part of its search for technologies that fight climate change.

There is a broad consensus among climatic scientists that priority too opposite is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the main cause of global warming.

But many scientists also believe that part of the solution will have to invent capture some of the gases that have already released their legs.

These projects, known as carbon capture, usually focus on capturing emissions at the fountain or taking them out of the air.

What makes Seacure interesting is that he is testing white, it could be more to extract carbon from the sea of the sea, since it is present in higher concentrations in the water than in the air.

To get to the entrance of the projects, you must travel the back of the Weymouth Sealife Center and Walk adapts to a sign that says “Caution: Moray Eels can bite.”

There is a reason why this innovative project has a leg placed here.

It is a pipeline that winds under the stony beach and to the Atlantic, sucking sea water and taking it to the Hore.

The project is trying to eliminate water from water could be a profitable way to reduce the amount of climate heating gas in the atmosphere.

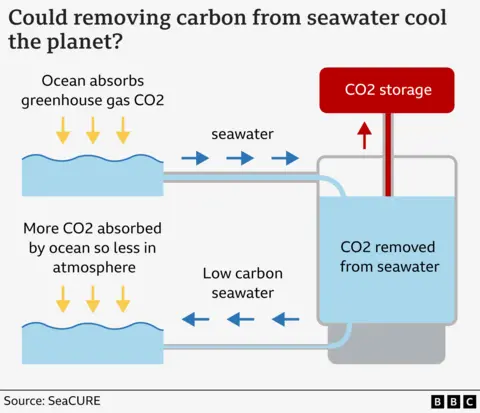

Seacure processes seawater to remove carbon before pumping it towards the sea, where it absorbs more CO2.

We are the first transmission journalists to visit and Professor Tom Bell of the Marino Laboratory of Plymouth has the task of showing us.

He explains that the process being part of seawater to make it more acidic. This encourages carbon that dissolves in seawater to become a gas and be released in the atmosphere as CO2.

“This is the stripper of seawater,” says Professor Bell with a smile while we fold a corner.

The “stripper” is a large stainless steel tank that maximizes the amount of contact between acid seawater and air.

“When you open a soft drink foam, that’s the CO2 that comes out.” Professor Bell says. “What we are doing extending sea water on a large surface. It is a bit like pouring a drink on the floor and allowing CO2 to get out of sea water very fast.”

The CO2 that emerges in the air is absorbed and then concentrated with coconut shells ready to be stored.

Low carbon seawater has alkali added to it to neutralize the acid that was added, and then pumps a current that flows towards the sea.

Once back at sea, it begins to absorb immediately to more CO2 of the atmosphere that contributes in a very small way to reduce greenhouse gases.

There are already much more developed carbon capture technologies that take the carbon directly from the air, but Dr. Paul Halloran, who directs the project, tells me that the use of water has its advantages.

“Seawater has a lot of carbon compared to the air, approximately 150 times more,” says Dr. Halloran.

“But it has different challenges, the energy requirements to generate the products we need to do this from sea water are huge.”

At present, the amount of CO2 that this pilot project is eliminating is small, at most 100 metric tons per year, that is, the carbon footprint of approximately 100 transatlantic flights. But given the size of the world’s oceans behind Seacure, he thinks he has potential.

In his submission to the United Kingdom government, Seacure said that technology had the potential to massively expand to 14 billion tons of CO2 a year if 1% of the world’s sea water was processed on the surface of the ocean.

For that to be plausible, the entire process to strip the carbon, would have to be fed by renewable energy. Possible by solar panels in a floating installation in the sea.

“Carbon removal is necessary. If you want to reach net emissions of zero and net zero emissions are needed to stop higher heating,” says Dr. Oliver, which are part of the intergovernmental panel on climate change and an expert in carbon capture.

“Capture directly from seawater is one of the options. Capture it directly from the air is another. Basically, there are 15 to 20 options, and in the end the question of what to use, of course, will depend on the cost.”

The Seacure project has 3 million government funds and is one of the 15 pilot projects backed in the United Kingdom as part of the efforts to develop technologies that capture and store greenhouse gases.

“Eliminating greenhouse gases from the atmosphere is essential to help us achieve net zero,” says Energy Minister Kerry McCarthy. “Innovative projects such as a University of Exeter play an important role in the creation of the green technologies necessary for this to happen, while supporting qualified jobs and increases growth.”

Exeter University

Exeter University‘Some impact on the environment’

There is also the question of which a large amount of carbon low water would make the sea and the things that live in it. In Weymouth it springs from a pipe in so small quantities that it is unlikely to have any impact.

Guy Hooper is a doctoral student at the University of Exeter and is investigating the possible impacts of the project. He has been exposing sea creatures to low carbon water under laboratory conditions.

“Marine organisms trust carbon to do certain things,” he says. “Therefore, phytoplankton uses carbon for photosynthesize, while, like mussels, they also use carbon to build their shells.”

Hooper says that the first indications are that massively increasing the amount of low carbon water could have some impact on the environment.

“It can be Damag, but there could be ways to mitigate that example through the previous production of low carbon water. It is important that this is in the discussion from the beginning.”